Features -- Hanoi -- 22 January 2017 -- Unless cited, photos are from 20 October 2016, 6 weeks before the BRT opened.

Vietnamese version - phiên bản tiếng việt

Hanoi BRT project background

The Hanoi BRT was in planning since late 2004,[docs] around the same time that Far East Mobility experts began the planning and design of the Guangzhou BRT, which opened in February 2010. Hanoi's 14.5km, 23 station BRT corridor finally opened a dozen years after the planning started, on 31 December 2016. During that time the Hanoi BRT project received the most intensive World Bank consultant and staff expert input of any BRT project in Asia and possibly the world.

As well as intensive input by staff experts over a decade, the World Bank hired consultants for all stages from the earliest project conception through to the project operation. The World Bank provided BRT design services and supervision of the BRT implementation. In 2005, with World Bank funding, PADECO CO LTD (Japan) prepared a ten year plan for BRT development which established some key project parameters and made corridor recommendations. On 18 April 2008, EGIS BCEOM INTERNATIONAL SA (France) and ING INGENIERIA SA (Colombia) were awarded a US$4.4 million contract for design services. On 9 November 2012, WILBUR SMITH ASSOCIATES INC (United States), INTECH JSC (Vietnam), GETINSA INGENIERIA VIETNAM CO LTD (Vietnam) and GETINSA INGENIERIA SL (Spain) were awarded a US$1.52 million contract for construction supervision. MVA ASIA LTD, a SYSTRA SA (France) subsidiary, was heavily involved in the critical design stages of the project and also carried out an environmental assessment of the BRT project realignment in 2013.[ref]

The Hanoi BRT project received the most intensive World Bank consultant and staff expert input of any BRT project in Asia and possibly the world.

The World Bank approved the project for funding on 3 July 2007 and the BRT project component cost was US$99.88 million, with a further $10.49 million for institutional capacity development.[ref]

The end result of the Hanoi BRT is a system which is in many ways a throwback to the design and planning problems of the Transjakarta Busway, though Transjakarta at least had the excuse of being Asia's first BRT project implemented in 2004 under a very tight schedule and limited design and construction budget, and without the benefit of substantial international expert involvement in planning and design. No such excuses can be used by the World Bank for the Hanoi BRT. Key features of the project are problematic and deeply flawed. Other cities should learn from this experience, and it is with this learning objective that this article is provided.

Opening ceremony for the Hanoi BRT on 31 December 2016. Source: http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/society/170457/hanoi-officially-launches-rapid-buses.html.

Opening ceremony for the Hanoi BRT on 31 December 2016. Source: http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/society/170457/hanoi-officially-launches-rapid-buses.html.

Mixed traffic incursion into the BRT lanes. Source: http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/society/170657/hanoi-brt-bus-collides-with-car.html.

Mixed traffic incursion into the BRT lanes. Source: http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/society/170657/hanoi-brt-bus-collides-with-car.html.

Lane dividers are being installed in some sections of the corridor. Source: http://tuoitrenews.vn/society/39211/lane-barriers-installed-on-hanoi-brt-route-as-markings-prove-ineffective.

Lane dividers are being installed in some sections of the corridor. Source: http://tuoitrenews.vn/society/39211/lane-barriers-installed-on-hanoi-brt-route-as-markings-prove-ineffective.

BRT corridor selection

One of the key decisions about any BRT project is the corridor alignment. With the wrong corridor alignment, a BRT project can be doomed to fail regardless of the later planning and design decisions. Conversely, an excellent BRT corridor selection will help to set a project up for success.

Most cities select BRT corridors in central, congested areas where the BRT project is expected to provide a benefit, but a few cities have implemented BRT systems in corridors which minimize or eliminate any chance of success. One such city was Chongqing, where the BRT system opened in 2008 and was finally demolished in July 2012 after years of low ridership. Another is Bangkok, where the Skytrain extension to Talat Phlu which opened in February 2013 has rendered the BRT corridor redundant for most passengers. Ridership fell from 1,200 passengers per hour per direction at the peak point in 2011 to just 200 pphpd in January 2017. This is the second lowest passenger throughput recorded by Far East Mobility worldwide, with only Kuala Lumpur lower.

The BRT could have included services that run to other parts of the city ... which would enable the corridor to serve a wider range of trip patterns even while overlapping substantially with the metro line.

The Hanoi BRT corridor selection is possibly not as poor as in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur or Chongqing, but is largely parallel with one of Hanoi's metro lines which is currently under construction. When that metro line opens, which is expected to be in 2018, it is highly likely that the ridership of the Hanoi BRT, already low, will be decimated. After the metro opens in a year or two, it is hard to see officials persisting with segregation of the BRT lanes with what is sure to be very low passenger demand.

The Hanoi BRT corridor selection problem of parallel operation with the metro is largely caused by the operational concept and design limitations, which means that BRT services will be constrained to the BRT corridor. With a better operational design, the BRT could have included services that run to other parts of the city and are not constrained within the BRT corridor, which would enable the corridor to serve a wider range of trip patterns even while overlapping substantially with the metro line.

An unfortunate aspect of the BRT corridor selection which compounds the problem of metro overlap is that the BRT corridor in the south passes by large expanses of farmland, low density housing and even a large cemetary, whereas the metro corridor, only 1.3km away, passes through a very dense urban corridor with high local demand. Planners may argue that the farmland and low density housing will be densified and have high future demand. However, the problem with this approach is firstly that if the demand will be ready in ten years, it would be far better to build the BRT there in ten years rather than now. Secondly, the BRT design capacity is so low and the system so unattractive, that only a very small proportion of any future demand will be accommodated by the BRT.

Hanoi BRT line (stations in red) and the metro line currently under construction (stations in blue).

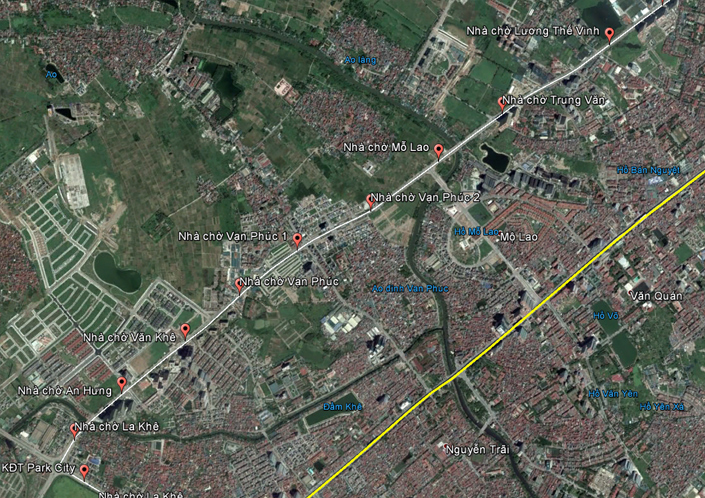

The metro corridor, in yellow, passes through dense urban areas. The BRT corridor, in white with stations marked, passes through farmland and low density housing.

The metro corridor, in yellow, passes through dense urban areas. The BRT corridor, in white with stations marked, passes through farmland and low density housing.

Hanoi BRT station underneath an elevated metro line. The metro is under construction, and is expected to open next year.

Hanoi BRT station underneath an elevated metro line. The metro is under construction, and is expected to open next year.

BRT operational design and vehicles

The World Bank's Hanoi BRT project does not really have an operational design. It is essentially a 'trunk-only' BRT line with a single bus route running up and down the corridor. The operational design, such as it is, is provided on the Hanoi BRT website and is shown below.

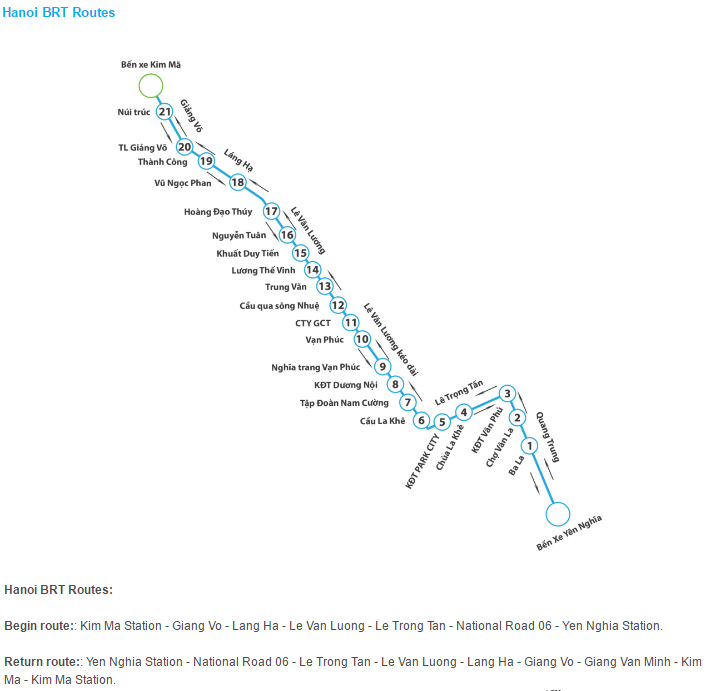

Hanoi BRT 'operational design'. The system features one service going back and forth up and down the BRT corridor. Source: http://hanoibrt.vn/en/hanoi-brt-route/hanoi-brt-route-map

Hanoi BRT 'operational design'. The system features one service going back and forth up and down the BRT corridor. Source: http://hanoibrt.vn/en/hanoi-brt-route/hanoi-brt-route-map

Hanoi's BRT station design precludes the use of any of the already-operating right-side-door buses in the city in the BRT system.

Hanoi's BRT station design precludes the use of any of the already-operating right-side-door buses in the city in the BRT system.

The proposed BRT operational design as stated in the MVA Asia report[pg 23] and as apparently reflected in the extremely low capacity station design, stipulates a short term BRT bus flow of 12 per hour in two directions in the first year, and 40 buses per hour in two directions in subsequent years, with BRT buses assumed to have a 60 passenger occupancy. This corresponds to a frequency of 6 buses per hour in a single direction in the first year, and 20 buses in a single direction in subsequent years. With only 20 buses per hour in a single direction, even assuming each bus has 60 passengers, the peak throughput of the system will be only 1,200 passengers per hour in a single direction. A mixed traffic lane with high motorcycle volume can carry more than 3,000 pphpd. Even in the most optimistic scenario, where the BRT had 40 buses per hour in a single direction (which is double the planned frequency), each carrying 60 passengers, the BRT lane would carry only 2,400 passengers, which is less than a mixed traffic lane. In short, the Hanoi BRT will never provide a net benefit in terms of increased roadway person-throughput. If the demand ever did increase to justify or require more than 40 buses per hour per direction, the BRT system would already be at the capacity limits of the very low capacity station design.

With only one narrow door at the front of the right side, the BRT buses cannot practically be used at regular bus stops.

Based on a seminar in October 2016, the World Bank's response to these concerns, along with the consultants leading the design of low capacity BRT systems in Saigon and Danang, is that BRT is needed to encourage two-wheeler users to switch to buses and to change travel habits. The problem with this argument is that even if passengers were somehow persuaded to shift to a BRT system with no operational flexibility, poor station access, no modal integration and other key limitations and deficiencies, the BRT system would not be able to accommodate them. If the BRT lane was just used as an exclusive motorcycle lane, it would carry at least double the maximum number of passengers that can be carried by the Hanoi BRT system, considering the design limitations.

With regard to the BRT vehicles, the World Bank's BRT consultants and experts evidently have a pet preference for BRT buses with a floor height of around 0.7m. The Hanoi BRT station platform height is 0.65m and the BRT buses have two doors in the left side of the bus, but only one narrow door at the front of the right side. As a result, these BRT buses cannot practically be used at regular bus stops, further locking in the Hanoi officials to the inflexible BRT operation. If the BRT were abandoned, the buses could not practically be used in regular kerbside bus operation. This failure to ensure BRT buses which can operate on and off the BRT corridor is another critical design failure of the World Bank's Hanoi BRT project. Meanwhile the 0.65m station height ensures that the lower entry recently procured regular buses cannot operate at the BRT stations, further reducing operational flexibility.

BRT station design

BRT station design is one of the most critical aspects of any BRT system, and the Hanoi BRT builds the system's inevitable failure into the BRT station itself, unfortunately meaning that it may not be possible to salvage the system short of demolishing and rebuilding the stations. The stations fail on multiple levels. Each aspect individually is a critical design and planning flaw, and the Hanoi BRT manages to combine all of these critical flaws into one system. Critical problems and flaws include:

- BRT station access

- BRT station doors

- BRT station length, width and height

- Lack of modal integration.

Each is briefly discussed in turn.

BRT station access

The BRT station access design and planning in the Hanoi BRT was very poor, or more accurately was seemingly non-existent. The poor station access will greatly reduce the appeal and ridership of the system. With long detours imposed on passengers wishing to access many stations, including steep and unpleasant stairs to access 7 of the 23 stations, and questionable speed benefits due to mixed traffic intrusion into the BRT lanes in congested locations, BRT passengers would probably have been better off at the regular kerbside bus stops which at least did not impose onerous additional walking distances and stairs.

It is hard to believe that this poorly accessible BRT will attract car or motorcycle users, and even existing bus users are likely to consider shifting to other modes.

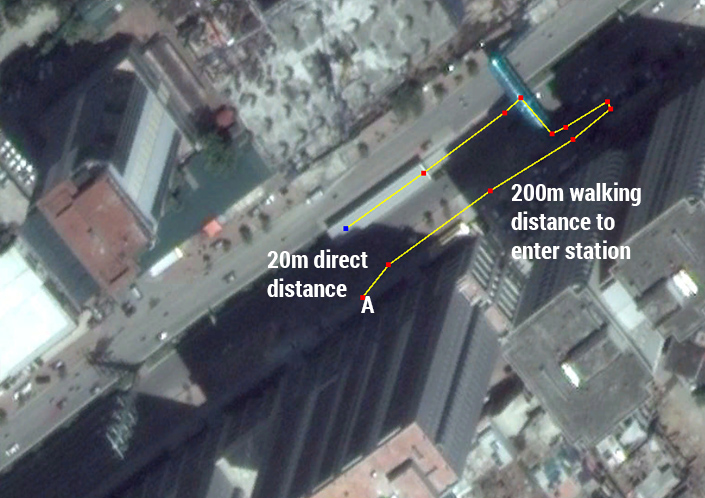

Some of the Hanoi BRT stations have street level access, but many of these impose long additional walking distances on passengers by forcing them to walk to an adjacent intersection. The seven stations featuring pedestrian bridges have steep stairs and only one access ramp at each foot of the stairs, instead of two. This results in long detours for pedestrians to enter the BRT stations. In the example of Nhà chờ Khuất Duy Tiến station below, the direct distance from the point labelled 'A' to the BRT station boarding area is 20m, but the walking distance is 200m, a extremely large detour factor of ten. Where BRT station access is at street level rather than via a bridge, the detour factor is sometimes even larger. At the Nhà chờ Hoàng Đạo Thúy BRT station shown below, the straight line distance is 20m but the walking distance is 250m. For many passengers, the impact of these additional walking distances - and stairs - will negate any speed benefits of the BRT.

Yet another very significant negative impact of these walking distances is the weather. When Far East Mobility saw the Hanoi BRT stations in October 2016, the hot, sunny weather and lack of shade or weather protection made the detours even less pleasant. Although the bridge structure itself is covered, the walk to access the bridge at the side of the road and then from the bridge to the BRT platfom is not covered. It is hard to believe that this poorly accessible BRT will attract car or motorcycle users, and even existing bus users are likely to consider shifting to other modes.

BRT station access at Nhà chờ Khuất Duy Tiến station. Passengers need to walk 200m to access a boarding area that is only 20m away, and go up and down two sets of stairs.

BRT station access at Nhà chờ Khuất Duy Tiến station. Passengers need to walk 200m to access a boarding area that is only 20m away, and go up and down two sets of stairs.

BRT station access at Nhà chờ Hoàng Đạo Thúy station. Passengers need to walk 250m to access a boarding area that is only 20m away, a detour factor of 12.5.

BRT station access at Nhà chờ Hoàng Đạo Thúy station. Passengers need to walk 250m to access a boarding area that is only 20m away, a detour factor of 12.5.

Access to the Nhà chờ Văn Phú station. As with the other bridges, the bridge has access stairs in only one direction. A passenger coming from the building directly opposite the station, 20m away in a straight line, will need to walk an additional 100m-200m and up and down two sets of steep, narrow stairs in order to access the BRT station.

Access to the Nhà chờ Văn Phú station. As with the other bridges, the bridge has access stairs in only one direction. A passenger coming from the building directly opposite the station, 20m away in a straight line, will need to walk an additional 100m-200m and up and down two sets of steep, narrow stairs in order to access the BRT station.

In addition to all the other problems, the stations are not wheelchair accessible.

In addition to all the other problems, the stations are not wheelchair accessible.

The stations with bridges all feature an inexplicably large gap between the foot of the bridge and the entrance to the station, which is exposed to the weather and imposes additional walking distances. Perhaps the bridge ramp was supposed to be less steep, so that the ramp would extend all the way to the station entrance? In this case, what happened to the construction supervision?

The stations with bridges all feature an inexplicably large gap between the foot of the bridge and the entrance to the station, which is exposed to the weather and imposes additional walking distances. Perhaps the bridge ramp was supposed to be less steep, so that the ramp would extend all the way to the station entrance? In this case, what happened to the construction supervision?

BRT station doors

Few BRT stations in the world have a lower design capacity than the Hanoi BRT. In Asia, probably only Ahmedabad, with a single dedicated door, has a lower design capacity. Stations can accommodate boarding and alighting at only two doors at once, which effectively rules out using articulated buses. Only one bus can dock at one time, so if two buses arrive at a station, the second bus has to wait for the first bus to finish boarding and alighting before docking at the station. This critical design limitation means that the Hanoi BRT cannot exceed more than about 40 buses per hour in a single direction without experiencing significant queuing delays at the stations.

Few BRT stations in the world have a lower design capacity than the Hanoi BRT.

Hanoi's BRT stations have only two doors in each side.

Hanoi's BRT stations have only two doors in each side.

BRT station dimensions

The BRT stations are 30m long (35m including the roof overhang) and either 4m or 5m wide. With only two doors and likely very low passenger demand, the severe limitations these stations impose on station boarding and alighting capacity may not even be noticed. If, however, new lines are added and ridership increases, the capacity limitations of these very small BRT stations will become quickly apparent.

For some reason the World Bank's BRT experts and consultants prefer BRT stations with a 0.65m platform height, and doors in only the left side of the bus. A less flexible bus and station configuration is hard to imagine. The buses can only operate at those 0.65m high station platforms and cannot operate outside the BRT corridor.

Lack of modal integration

The lack of any significant modal integration beyond placing a BRT station at a bus terminal and near future metro stations is understandable in that the Hanoi BRT cannot accommodate any significant shift from motorcycle (or other modes) to BRT, given the design limitations.

World Bank: "[The Hanoi BRT] will prove effective in meeting local commuters’ demand and easing traffic congestion."

BRT design by negotiation and World Bank fiat rather than technical considerations

When the various design limitations of the Hanoi BRT were raised by Far East Mobility in a World Bank Global Environment Facility (GEF) seminar in Hanoi in October 2016, the World Bank's senior Southeast Asia regional representatives in attendance did not respond. Jung Eun Oh, World Bank Senior Transport Economist and the Cluster Leader for the Transport Sector in Vietnam, interceded to cut off discussion, which was probably understandable given that the system was due to open within two months. (Ms. Jung Eun Oh is also the team leader for the ongoing Ho Chi Minh City BRT planning, and assured the media and public via the official Vietnam News Agency of the World Bank's strong confidence in the Hanoi BRT a couple of weeks prior to the system opening, insisting that the Hanoi BRT "will prove effective in meeting local commuters’ demand and easing traffic congestion.") In a similar vein, the consultants hired by the World Bank for BRT planning and design in Ho Chi Minh City emphasized that what was required was a positive outlook and attitude when dealing with the very challenging problem of how to shift people from motorcycles to buses. BRT had to be tested and tried out in the context of such high motorcycle usage. (Far East Mobility's view is that what is required is excellent BRT planning and design, not a positive attitude or willingness to experiment.)

In our experience with BRT planning in many cities, the Asian Development Bank tends to make key decisions in BRT planning based on technical considerations, whereas the World Bank appears to approach BRT planning more as a negotiating process, placing great weight on their own often unsubstantiated opinions and impressions.

In the ADB BRT projects in Lanzhou and Yichang, both of which are very successful, the key design and planning decisions were all led by technical considerations, as were the key decisions in the Guangzhou BRT planning and design. The World Bank's project managers often seem to take a quite different approach. For example, in the GEF seminar in October 2016 Far East Mobility raised various problems with the Hanoi BRT design, and suggested that a corridor like this should have multiple BRT routes entering and leaving the BRT corridor, perhaps more than ten. The World Bank Vietnam transport sector cluster leader, despite having no experience with BRT implementation prior to Hanoi and citing no study or data as a basis for her views, simply proclaimed that ten would be too much, but that two or three might be a good idea. The point is: this is not the kind of key decision that can be made by negotiation, or by World Bank fiat, or based on the gut feeling of a World Bank transport expert. It must be based on reliable demand and operational analysis and it must be reflected in the system design.

When the station access detours are factored in, it is questionable whether the BRT provides faster trip times than regular buses would provide along the same route, especially when considering that most trips use only a portion of the BRT corridor.

BRT development in Hanoi and Vietnam

One of the primary rationales of a BRT project is to improve bus speeds, and the planned speed for the BRT was 29.4km/hr or 30 minutes for a single trip[ref] as reported before the system opened. After the system opened, the actual operating speed was 16km/hr, or 56 minutes for the trip, and planners revised the target speed down to 19.6km/hr (45 minutes for the trip) when lane dividers are installed. When the station access detours at many stations are factored in, it is questionable whether the BRT provides faster trip times than regular buses would provide along the same route, especially when considering that most trips use only a portion of the BRT corridor. It is clear also that allocating exclusive space for BRT buses in that corridor means that the non-BRT buses operating in that corridor, serving different areas of the city, will be adversely affected by increased congestion. Motorcycles, taxis, coaches, delivery vehicles and other road users will all be adversely affected by the reduced space in some critical locations.

In many cities, when BRT is implemented it is possible to improve traffic for all modes, because BRT can solve the problem of bus stop congestion and take significant numbers of buses out of the mixed traffic and into segregated lanes. With very low bus flows in the corridor before the project, this is not the case in Hanoi, and the imposition of segregated lanes in congested locations will affect all road users negatively except for the low volume of BRT passengers. This in itself can be justified if the project delivers larger network benefits or establishes a future trend of transit priority and a system which can over time accommodate a large shift from other road users, or if a design goal is to reduce the roadway capacity as a form of traffic management or demand management measure. Unfortunately, with the Hanoi BRT's design and operational limitations, there is neither potential nor capability of accommodating any significant shift from other modes.

Another unfortunate impact of the Hanoi BRT is that limited attention, funding and political will resources have been poured into a BRT system which will never serve more than a tiny niche of the transit market in the city, and this is likely to continue if officials double down on misguided approaches by adding new BRT lines with a similar configuration; an approach which is virtually guaranteed by the lock-in effect of ongoing BRT bus procurements. The non-BRT bus sector will receive far less priority, attention and resources than the BRT, despite carrying a far greater proportion of transit passengers, and the overall mode share of public transport in Hanoi will suffer accordingly.

Worryingly for those cities, the World Bank is leading BRT planning in both Ho Chi Minh City and Danang.

Apart from the direct negative impacts on many road and transit users in Hanoi, the most serious and unfortunate aspect of the World Bank's Hanoi BRT is that the development of BRT in Hanoi and probably in Vietnam is very likely now consigned to years of vicissitude accompanied by an ongoing gradual deterioration in public transport mode share until the BRT system is eventually decommissioned. The traveling public will rightfully question why a lane is being segregated for BRT traffic when that lane only has one bus every five or ten minutes. Such media articles and concerns are already apparent. The government will initially dig in, trying to insist on BRT lane segregration in order to save face and assuage the World Bank. Eventually, however, the futility of enforcing BRT lanes for such low passenger throughput will be so apparent that officials will probably face reality and abandon the Hanoi BRT. In the meantime, the government may struggle for years to enforce the BRT's exclusivity, all to no useful end.

The early signs are that the government is indeed digging in, and has even announced plans for additional BRT corridors. Unfortunately, the new corridors seem to be being approached in the same way as the initial corridor, thinking only of running buses along a particular corridor rather than accessing other parts of the city.

The World Bank and project supporters will probably argue that when the Hanoi BRT is supported by additional lines and corridors, the overall ridership will rise as passengers can access more areas around the city, including through integration with the metro lines currently under construction. The problem with this argument, though, is that the Hanoi BRT has little capacity to accommodate additional services or increases in ridership even if new corridors are added.

It is possible that the World Bank will acknowledge the many mistakes made in the Hanoi BRT and act to mitigate them, and drastically change direction when it comes to planning any new BRT corridors. Far more likely, though, is that their calcified approaches to BRT which seem to draw from inappropriate North American or European experience, will prevent any such frank reappraisal, and instead that they will try to mitigate some of the worst aspects while expanding the same flawed model to other corridors and probably other cities in Vietnam. Worryingly for those cities, the World Bank is leading BRT planning in both Ho Chi Minh City and Danang.

The Hanoi BRT experience shows that big budgets and prominent names in the form of consulting and engineering firms, or in the form of World Bank experts, are not a substitute for sound BRT planning and design.

Some lessons learned

The Hanoi BRT experience shows that big budgets and prominent names in the form of consulting and engineering firms, or in the form of World Bank experts, are not a substitute for sound BRT planning and design. The people of Hanoi will unfortunately pay the price for the errors and missteps throughout more than a decade of intensive World Bank invovlement in the Hanoi BRT planning, design and implementation. And with such intensive involvement in all aspects of the project from the earliest stages, the World Bank does not really have any excuses for the poor outcome. Prior to the commencement of operation in October 2016, the World Bank was advertising their ownership of the project in some large display signs located along the BRT corridor. It is not known if these signs are still on display after the system opened.

A World Bank / Hanoi BRT sign on display in the BRT corridor in October 2016, before the system opened. After seeing the system 6 weeks prior to opening, Far East Mobility advised the attending senior World Bank officials that the Hanoi BRT would fail and that they should already be in damage control mode rather than promoting the system to the public.

A World Bank / Hanoi BRT sign on display in the BRT corridor in October 2016, before the system opened. After seeing the system 6 weeks prior to opening, Far East Mobility advised the attending senior World Bank officials that the Hanoi BRT would fail and that they should already be in damage control mode rather than promoting the system to the public.

The Hanoi BRT is in many ways similar to the main corridors of the Transjakarta Busway, except that Transjakarta has a better corridor, a more sophisticated operational design, and significantly higher capacity stations (after stations in the main corridors were retrofitted to accommodate 18m BRT buses with three doors). The one seeming advantage that Hanoi has over Transjakarta is that the construction quality is much higher, reflecting the much higher cost. Ironically, this factor may actually be a disadvantage. When Transjakarta stations needed to be rebuilt or renovated to accommodate 18m BRT buses with three doors, the process was relatively inexpensive given the less substantial initial station construction. In Hanoi's case it is more likely that the only way to address the major problems and capacity limitations is to entirely demolish the stations and rebuild them. If the Hanoi BRT had opened around the time of the Transjakarta Busway in 2004, although still inexcusable, at least the design and planning shortcomings would be more understandable.

Just because a project is labelled 'BRT' does not mean that it provides a superior service to regular buses, or any net benefit to road users or the city... BRT only provides benefits if it is well planned and well designed.

In many ways, this article probably paints a rosier picture of the Hanoi BRT than the grim reality. For example, when assessing the passenger occupancy for comparative purposes, we used figures of 60 passengers per bus. Far more likely is that bus occupancy and hence passenger throughput is much lower, and will be further decimated when the metro line opens. We have not yet seen the Hanoi BRT in operation and can only refer to media reports, but the initial reports confirm the difficulties that should have been foreseen and prevented during the long planning stages.

Some proposed lessons learned from the World Bank's Hanoi BRT experience include:

- Just because a project is labelled 'BRT' does not mean that the project is good, or that it provides a superior service to regular buses, or that it provides any net benefit to road users or the city. In the case of Hanoi, given the station access difficulties, it is probable that the BRT passengers would have been better off with just regular kerbside bus stops, and the city would surely have been better off investing the funds in conventional bus system development rather than BRT. BRT only provides benefits if it is well planned and well designed, which is unfortunately not the case in Hanoi.

- Cities and BRT planners should not allow World Bank experts and consultants to railroad the BRT planning process and impose their own pet ideas. When it comes to key aspects of the BRT planning, planners and designers need to push back against ill-advised approaches.

- BRT project developers should minimize or eliminate risk by ensuring a good project plan and design. 'Keeping a positive attitude' and 'hoping for the best' is not a good approach to BRT planning. City officials should demand assurances about project viability and insist on clear answers to concerns, and strong technical justifications for decisions. Admittedly, this is often culturally difficult in Asia, where there is a tendency to be respectful and deferential to 'senior' foreign experts associated with high profile organizations such as the World Bank.

- As Hanoi's experience shows, just putting in place the correct procedures with a high supporting budget does not by itself ensure a good project outcome. In Hanoi's case, the sustained input by consulting firms over a long period together with substantial supervision contracts were sound approaches, at least on paper.

- The BRT implementation should include a separate project component and team focusing on BRT supervision and implementation support, and should not look to combine all aspects of the technical design and supervision under a single contract and team. This approach of combining all aspects under one large contract may be easier to administer, but it will tend to rule out input by smaller firms specializing in BRT in favour of the kind of larger firms that worked on the planning and design of the Hanoi BRT.

- Cities should not just assume that any large engineering firm can do a good job with BRT planning or supervision, no matter how big the firm or how impressive the firm's profile. BRT planning and design requires specialized skills and approaches.

Article by Karl Fjellstrom, Far East Mobility.